Part Two: The Vocabulary of Pluralism

In Part One, I introduced the idea that God-concepts are important — and not merely to theologians and religion scholars (about which, while theology and religious studies are allied fields, they are not the same. This Religious Studies page explains the matter well.)

In Part Two, I highlight the relevance of understanding theology in a multicultural society, and explain why this can and should matter — to you, and those you care about. And this, even if you consider yourself to be an avowed atheist.

In the Religious Landscape Study, the Pew Research Center found that 63% of Americans were absolutely certain that God exists, and 20%, fairly certain. On the world stage, in a 2019 study, the Pew Research Center surveyed 38,426 citizens in 34 countries, asking them whether God is necessary to morality, and found that the responses were correlated to education, income, a country’s economic development, and age, with individuals and nations of higher income and education, and younger respondents, viewing belief in God as less important overall.

For good or for ill, this “Global God Divide,” holds implications not only for individual belief systems, but extends to communities and geopolitics, both now and well into the future. Although atheism and agnosticism are also increasing in prevalence (in 2018 and 2019, 4% of Americans reported themselves as atheists and 5% as agnostics), the vast majority are believers.

But what should theology mean to you, the reader, if you have no interest in religion, or consider it to be akin to cultural superstition? Is it not sufficient to read about the latest religiously-motivated political debacle or view a re-run of 19 Kids and Counting and shrug, secure in the knowledge that this is not the way you and your family have chosen to live? Are Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins right to lambast religion and dismiss it whole-cloth?

I’d suggest an alternative to these options. In fact, if you have any interest in cultural or international affairs, or are an avid reader of the morning news, your intellectual and emotional toolkits need to contain more sophisticated and nuanced modes of understanding religion than you’ll find in books and videos that ridicule it and relegate it to the past.

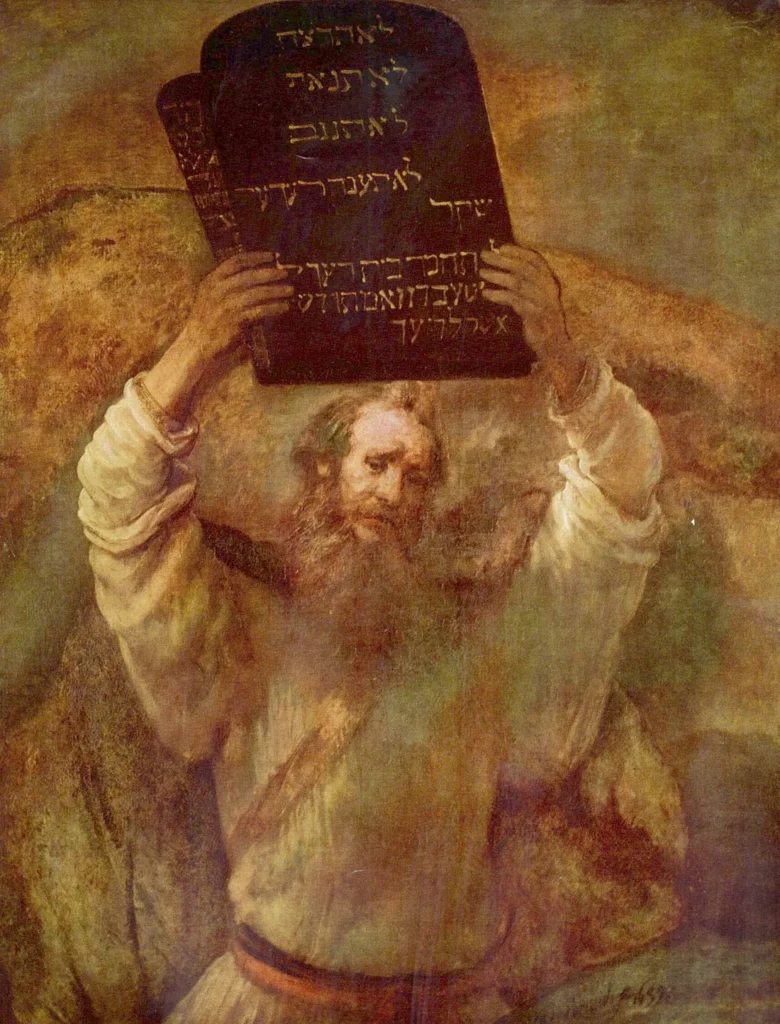

While you may never share any of the thousands of worldviews held by adherents of the world’s religions, it is important to know that religions and cultures are inextricably linked. Religious ritual, imagery, sacred texts, hermeneutics (interpretations of these texts), music, architecture, and moral codes have a significant presence in works by authors and artists as disparate as Shakespeare, Milton, Cynthia Ozick, Michelangelo, C.S. Lewis, Rembrandt, Hildegard of Bingen, and Sahar Mustafah.

Historically, religion is directly relevant to the rise of the city-state in Mesopotamia, colonial conquests, the evolution of jurisprudence, and today, to world governments and international relations, among too many other spheres to enumerate.

In short, whatever your religious beliefs, not having a nuanced command of the language of religion, or the ability to see the world from the confessional (believer’s) perspective, is to be left at a real disadvantage when it comes to understanding the flow of history, the artistic allusions, the interplay of cultures, and the complex dynamics that hold sway within a given culture. In brief, to relegate religious belief and praxis to the realm of the dismissible and irrelevant is to deny the powerful presence of religion in our world.

Returning to the specific matter of theology, then, what is it for? Moreover, why does it matter? Is it not sufficient to know that, for example, Jews believe in a personal God who bestowed the Torah to the Israelites via Moses? Unfortunately, no, it is not. Because, returning to my Facebook poll, for example, I learned that among the sixteen respondents, none actually believed in a personal God. While this was merely a straw-poll, it points to the likelihood that personal and collective theologies are changing, and that the religious realities on the ground, in specific countries, and within religions, are also evolving.

To ignore God-concepts, then, is to be blind to significant aspects of our world’s changing religious cultures — some of which play major roles on the world stage, and very possibly, in your own community, affecting your life and well-being. One example is the link demonstrated between COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and religion, which seems to suggest a conflict between “religious” and “scientific” worldviews. Yet another example along similar lines is related to anti-maskers and religion.

By contrast, to understand what religious adherents see as their relationships to their God or gods, to comprehend what is most important from their own perspectives, not your own, makes it possible to extend your sense of empathy. Thus extended, this empathy gives you the power to see further than dismissal or ridicule ever could. Viewed from this perspective, attempting to prove or disprove the existence and essence of a God or Gods, or worse, to point and laugh at a sacred text and poke holes in its historicity or logic, are missing both the point, and the opportunity to build bridges.

To come to understand beliefs (and consequent behaviours and rituals) you may see as irrelevant or somehow unworthy of a modern, scientific society, even without holding them yourself, can move mountains. Sometimes, empathy even makes it possible to persuade individuals and groups. Indeed, this willingness to engage with confessional/insider understanding is beginning to be effective in combating vaccine hesitancy, for example. The importance of understanding diverse belief systems also holds true in fields as far-flung as education and international relations.

More salient is the fact that the religion curricula that we may have been taught decades ago, in school, may no longer reflect the beliefs, rituals, and cultural dynamics taking place today. And that New York Times bestselling non-fiction tome debunking a world religion? Look more closely at it, and it’s almost always attacking a straw man.

By this, I mean to say that having read many of these, I’m no longer surprised at their frequent aggression, mean-spirited poking, and attempt to overturn God-concepts and religious texts. Rather, I am more concerned about their caricaturing of religions, reducing them to stereotypes and tropes that are easily torn apart. And once again, these activities miss the point. Flattening Judaism by presenting it merely as a religion that believes in a creator God, and pointing and laughing at the Book of Genesis, does not do justice to Jewish history, culture, rabbinic scholarship, or the lived reality and beliefs of Jews today. Nor does this reductionism represent Judaism in a nuanced way. The same is true when such authors lampoon other religions and their beliefs.

What’s a theology for, then? Understanding God-concepts and the phenomena connected to them is not merely for adherents. It is for teachers, parents, students, politicians, diplomats, health care practitioners, and anyone who cares about coming to understand the interpersonal and cultural patterns unfolding around us.

One example from my own practice. Years ago, I began to listen to Christian televangelists on my car radio, and to collect religious pamphlets wherever I saw them being handed out. A copy of The Watchtower being handed out in a subway station by Jehovah’s Witnesses? Why not? An evangelical tract about the importance of faith? Sure! A tract about Brahman published by a Vedanta group? Yes, please!

But why? What interest could I have in these materials? Am I seeking a new religion to replace my own? No. For my part, I’m simply always curious as to the ideas, the concepts, and even the rhetoric used to present God-concepts. And the wider the gap between my own beliefs and my new reading material, the better. The better to discern, that is. The better to think. And the better to understand other worldviews. It is a bit like being a detective or an anthropologist — ever-observant, picking up on cultural clues, putting judgment aside. Another perk? It’s free. (So is the public library.)

In summary, facing God-concepts in our culture is an opportunity. To co-opt the therapeutic language of Drs. John and Julie Gottman for a moment, we can either choose to turn away from these ideas, dismissing not only their possible existence, but their importance to our culture, or turn against them (the non-fiction attack literature approach). Another option, however, is to turn toward them. Not to become a believer, but to learn, and come to more fully understand worldviews that differ from our own, without judgment.

Once we accept the reality that God-concepts are here to stay, and that dismissing them is missing the point, we can begin to see them as potent lenses that anyone can try on and use to examine individual and cultural worldviews, and develop both empathy and understanding.

Understanding the mechanisms and elements of belief is simply that — a tool that can be used to build bridges between disparate understandings. This is true both interpersonally, and more broadly on the levels of culture and geopolitics. Ultimately, the way forward toward harmony in a pluralistic society will be forged by individuals — politicians and national interests that understand these tools, and know how to wield them thoughtfully and effectively.

Leave a Reply